Dave Hudsonhashingit.com |

Getting real with blockchain

Note 2020-03-06: An earlier, longer, version of this was published on Medium and LinkedIn. This version has been slightly edited to be a bit less of a sales pitch for my then-team, Solutions Engineering. I’m very happy to note that in the 14 months since the original article, the team has gone on to bigger and better things, continuing to help customers “get real” with Corda.

It’s pretty-much impossible to avoid the pronouncements in both the technical and mainstream press about how blockchain is going to change the world. Blockchain feels like the cure for every known ill in the world of computing. Take a couple of smart contracts three times a day and everything will be just fine. Haven’t we heard this sort of thing before, though? The details were different, but a myriad of other technologies promised equally radical futures. In far too many cases they were wrong, and the reality fell short of the hype. How, then, do we get real blockchain? More specifically, as I’m not pretending to be completely unbiased, how are we getting real with Corda?

Technology hype cycles

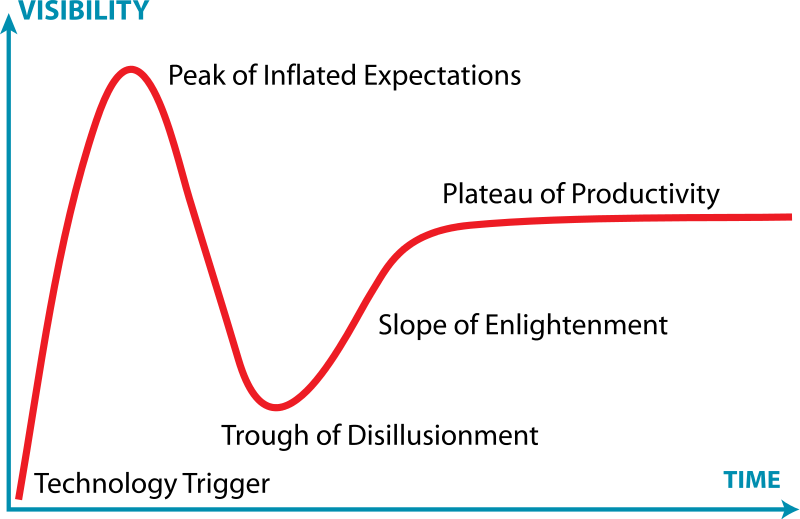

Technology developments tend to follow a common pattern, often known as the “hype cycle”. The figure below depicts the journey. It should be pretty familiar to many of us.

Technology Hype Cycle (By Jeremykemp at English Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10547051)

It’s not that early technology enthusiasts deliberately set out to oversell anything. They demonstrate how their particular technology can do amazing things, and how simple it is to use. Dig into the details, though, and we find far too many demonstrations are proofs-of-concept, or prototypes of solutions to oversimplified problems. The problem is the demos tend to look quite complete, so it’s far too easy for both their creators and their viewers to miss the size of the gap between them and production-viable solutions.

Production systems are much more complex. They have to address the full needs of a business, they have to integrate with other things, and they have to handle a whole range of failure modes. As a friend has often reminded me, “it’s easy to build things that work; it’s very much harder to build things that fail gracefully”. The transition to production, and thus to making the technology real, is often very painful. Early successes lead to an expectation that a technology is largely finished when, in practice, it’s often barely started at all. This trough of disillusionment can be very deep indeed.

This path to production is vital though. With understanding of production needs and production applications we start to see the emergence of useful software platforms.

What are platforms?

In the world of software, we often talk about “platforms”. What do we mean, though?

Platforms seek to extract the core of a technology, allowing that core to be used to solve many different problems. They make the efforts of a group of very talented designers and engineers available to everyone else to build on. Platforms focus on things that are really hard to get right, allowing anyone using them to avoid worrying about those things too.

Great platforms go far further. Not only do they offer capabilities and guarantees to software built on top of them, but they go to great efforts to avoid having too many opinions about how that software should work. They enable success without constraining that success too much. In doing so, they allow for innovations that did not have to be imagined by the platform’s designers.

For a technology like blockchain we have to start with a great platform. If our platform has too narrow a scope it can’t hope to fulfil everyone’s aspirations. Equally, a platform has to make a few decisions otherwise it has no value. If we want to solve valuable business problems then we have to design for the environment in which those problems exist, and any constraints that such businesses may impose.

Corda, a blockchain platform

Corda is an open platform that allows participants in a highly decentralised system to stay fully synchronized about facts that are shared between some or all of them. Superficially this sounds like a distributed database, but the key difference is the decentralisation. A distributed database is the property of one organisation or person, but a decentralised one has many owners. More importantly, unless those owners have reason to share everything with their peers then they shouldn’t have to do so.

Corda extends this. Once facts are shared into its decentralised ledger, they can be used to make other updates, potentially with other participants. Corda’s smart contracts constrain what those updates look like, so it can ensure that accidental or deliberate misrepresentation of the original facts will be caught and rejected.

Of course, there are many blockchain platforms that make claims to do this. What makes Corda more interesting from the perspective of “getting real” is that it was designed in conjunction with an incredibly challenging set of users. Corda is sometimes dismissed as a “blockchain for banks” but such observations miss that regulated financial institutions set a very high bar for success. They want to use technologies they can trust to have real business value, doesn’t needlessly share information with counterparts, that can be supported for decades, and will integrate with their existing infrastructure.

Corda has a “private by default” communication model, yet retains the flexibility to allow any set of participants to transact in arbitrarily complex ways without any impact on non-participants. It also extensively leverages the Java virtual machine (JVM) and SQL databases because of their proven longevity, broad adoption, and massive developer talent pool.

It’s easy to dismiss this as an over-conservative approach, but it’s worth asking ourselves a question. How many of the things we all take for granted actually rely on some action years, or decades in the future “just working”? If we buy an appliance with a 10-year warranty, then in 9 years we really want to be sure that any smart contract written now will still work as planned. How about buying property? We might not sell it for decades. What sort of design planning is needed in both our core blockchain platforms, and any applications written to use them, such that such longevity is both possible and plausible?

This isn’t to say that Corda is perfect, but it provides production-capable building blocks to let us solve business problems. We still have to build applications on top of it, and that’s the next challenge in getting real.

Production applications

Let’s say we want to build a CorDapp to solve a business problem for a group of different organisations. We’re going to end up writing code, building tests, having user acceptance, deploying, etc. These steps are common among technology projects, with proven best practices ready for us to embrace, but decentralised systems add some new wrinkles. To understand why we have to consider what our blockchain is doing for us, but also what it’s not doing for us.

Our group wish to use a blockchain because they desire a consistent view of the data they share. The logic that updates the decentralised ledger is identical for each participant and they all agree what’s being transacted and what it means. This means they’re all set on sharing the format of on-ledger representations of their transactions, and the contract code that allows for updates to take place, but they still all choose what, why, or when, they transact on a basis unique to each of them. If those decisions come from other systems then they will each need a unique strategy for integration, that matches their own established policies. Indeed, each of them will have their own unique policies around how their systems are integrated, deployed, operated, and evolved. It’s possible that we might be able to get them all to go live on the same date, but thereafter their own policies mean it may be very hard, if not impossible, to ever get all of them to coordinate the same technical steps at the same time ever again.

We already noted that in some cases we might need to enter data into our shared ledger now, but that will still lead to correct operation years, or decades, into the future. When we start to think about what’s represented on the ledger how can we ever be sure that our understanding now will meet all the future needs? We can’t, of course. Transactions may become subject to new regulations, such as GDPR, that introduced a huge swathe of restrictions, so we have to plan for evolving data in the ledger and the contract logic that controls it. While GDPR represented one particular privacy concern, when we think about sharing data with potential competitors then we’re probably also going to have to think carefully about what we share, and on what basis.

Now that we’ve anticipated the need to possibly have to update our shared data and code, we might ask who is going to decide on the needs for updates, and how will that process look? Each of our organisations might have differing views. What happens if we decide we want to introduce more participants? What if one of our original participants decides to exit this business and no longer wishes to be part of the blockchain network? What if we want to share our Corda network with other organisations for unrelated types of activity?

Blockchain offers many opportunities to reduce duplicated efforts across our group but comes with some new challenges. Some are conceptual, some technical, some organisational, some operational, and some project governance, but a blockchain doesn’t solve for any of these in itself. What’s required, instead, is to look beyond the core technology, get past the stage of demos and PoCs, and solve for the real problems that production systems have.

Looking Forward

Learning how to build and deploy successful decentralised applications isn’t easy, but, right now, this is one of the most interesting problems in software engineering. Like all interesting problems, things are not always straightforward.

Having led R3’s Solutions Engineering team for the last 18 months I have a lot of sympathy! Supporting customers build completely new decentralised systems can feel like being a therapist (yes, we feel your pain *), but the most rewarding aspect of working with any platform is seeing what other people are able to do with it.

The R3 NYC office, when they have that “aha” moment about how to help a Corda customer - well that’s what they tell me anyway ;-)

Acknowledgement

* Austin Moothart gets the credit for joking that Solutions Engineers should really be called “Solutions Therapists” and that “we feel your pain” - I’ve been laughing about it ever since